The most curious thing about Neil Gaiman's Sandman opus is that it really is as good as it's made out to be. With an army of artists at his side, Gaiman crafted what is, in my humble opinion, easily one of the top 5 comics stories ever told. By utterly revamping the idea of the The Sandman into a grand, myth-spanning being known as Dream or Morpheus, Gaiman opened up a gateway to storytelling without limits. That is precisely what is on display here in the third volume, Dream Country.

Rather than suggest we read the first volume (which was more of a horror comic teetering as it found its footing) or a later volume (which would require more context than time allowed), I latched onto Dream Country as the perfect example of what made The Sandman the seminal series it was. Collected in this slim trade are four stories that intermingle horror, comedy, fantasy, despair, and outstanding creativity. Most of all, they barely feature the titular character (except for the last tale, which doesn't feature him at all). I suspect that this method of storytelling will be familiar to those class members who read more than a handful of Spirit stories. Like Eisner and his masked do-gooder, the greatest strength of Morpheus might lie in his creator's boundless drive to tell stories.

The four seemingly disparate tales in this volume all revolve around the idea of dreams. These dreams require captured stimulus ("Calliope"), are the basis for powerful change ("A Dream of a Thousand Cats"), are granted in a bargain ("A Midsummer Night's Dream"), or seem unattainable and mournful ("Façade"). In any situation, dreams are the center of the Sandman mythos, so the title to this volume is exceedingly appropriate.

The first two tales, pencilled by Kelley Jones, show the range that this series is willing to take. In "Calliope," we are privy to a wicked deal to spark a novelist's creativity. This entry perhaps ties the most into the regular fabric of the series, as the Furies and Orpheus both factor in. This story also serves as a sort of hub of metaphors, as Dream's own bondage is mirrored here by the captured muse, and the tortured writer's bargain is a much darker version of the deal that Will Shakespeare will make in a few issues' time. "A Dream of a Thousand Cats" is an issue that tends to stick in the minds of many Sandman readers. I think this is the first (but not the last, no, certainly not the last) issue of The Sandman that made me cry when I first read it years ago. The sadness of the unnamed cat's tale really struck me because it didn't feel forced in any way, and she was such an audacious, powerful female character -- who is also a cat. Here Dream is a dark cat with brilliant eyes, and the issue doesn't feel like a "What If?" but like truth, a quality that was felt in the best of the 75 issues.

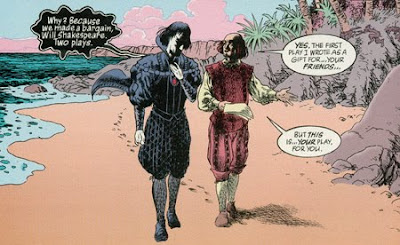

"A Midsummer Night's Dream" has the distinction of being the only comic to ever win the World Fantasy Award (not without controversy), and I can certainly see how it earned the prize. By framing itself around and within the famous play of the same name, Gaiman and collaborator Charles Vess get a lot of mileage out of a conventional size comic book. This story is one of those perfect mixtures of comedy and sadness that Gaiman is so adept at, with Robin Goodfellow and the rest of the faerie causing mischief even as Will Shakespeare's young son illustrates his skewed priorities. The end of the story, with its twisted lift from Shakespeare, gets me every time and inspired much of my love for the original play.

Finally, this volume includes "Façade," a story that I suspect readers won't respond to as well as the preceding three. I know that I hardly cared for Gaiman's collaboration with Colleen Doran the first time I read it, but my feelings have changed with time. This melancholy tale of a forgotten Silver Age heroine shows Gaiman's ability to mature a character without going overboard. Rainie becomes more complex and real in these 22 pages than she ever did in her myriad adventures before, even if the story is a heartbreaking one. It also doesn't even feature Morpheus, though the real breakout star of the series drops by at the end. yes, Death is probably the most affecting character to be spawned in Gaiman's epic run. The idea of Death as a spry young goth girl changed everything when she was introduced and provided the genesis for some of the strongest stories Gaiman has ever told. While Death certainly has one of the single greatest lines in all of comicdom (I won't spoil it here), I'll be damned if her greeting on the telephone at the end of this issue doesn't bring the tears right back up.

And I suppose that's one of the most honest things I can say about the quality of The Sandman. I laugh and I cry every time I work my way through a story, no matter how many times I have read it before. I'm so grateful that Gaiman was able to bring this book to the public at a time when overly rendered, grotesquely muscled murderers ruled the comics scene. As comics were striving to become "mature" by virtue of more guns, more blood, and more sex (not to mention more pouches), Gaiman and crew were effortlessly putting the foundation into place for true mature storytelling. Vertigo wouldn't exist in nearly the same form it currently does if Sandman had never been published, and the world would be much worse for it. Luckily, enough of us still dream about the characters that Gaiman and his team of artists created to keep them around.

No comments:

Post a Comment