Reading the first collection of G. Willow Wilson and M.K. Perker's Air is a bit like reading letters from another country: everything is a bit off, it's difficult to understand and follow, but it's all very enticing and you want to know more. Air follows an acrophobic flight attendant swept up in an international (supernational?) conspiracy to... Well, I'm not entirely too sure what the conspiracy really is at this point. I know it involves a forgotten kingdom called Narimar, an ethnically shifting paramour, the shadowy Etesian Front, a winged serpent, a fuel-free engine, some mentions of dominatrixes, marigolds, reality-bending flying machines, and Amelia Earhart. And that's all in the first five issues. Sound like a lot? It is.

I read this first volume of Air in three chunks with short breaks in between. After just finishing it, I'm a little confused about what became of the angry female Front member and the priest, and I can't recall if we found out who the pilot of the "flying palace" actually is quite yet. If I were attempting to follow this series with a month lapse between each issue, I'm not sure I would have the will to continue. I applaud Wilson for keeping things moving and introducing a lot in a small amount of time without feeling horribly rushed, but these sorts of Vertigo books benefit from more of a slow build. As comic readers, we can accept some extraordinary circumstances, but I wish Wilson had gotten more milage out of defining how odd this world is to its regular inhabitants. Blythe and her colleagues seem entirely too ready to adapt to every crazy thing that happens along the way, and it lowers the impact of the zanier elements for me as a reader. I have no concept of what life was like before the zaniness set it, so everything has less of an impact on me. I could see how Blythe's reactions would be more open, but Fletcher or Mrs. B could have really filled that role to help contextualize Air's world and strengthen character at the same time. Ultimately, I find the elements of Air very interesting, but I am having trouble finding my window into the world.

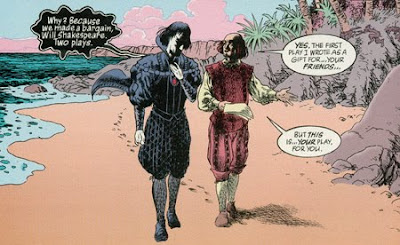

The art, provided by the Turkish M.K. Perker, is solid but I didn't personally feel it was exceptional. As pointed out by a review quoted on the Wikipedia page for Air, his work is very reminiscent of an early Brandon Peterson. I'm a fan of Peterson's hyper-detailed, heavily cross-hatched work, but Perker's is less meticulous and occasionally inconsistent. Faces tend to distort, and detail rapidly disappears as the panel pans outward. I feel that Air suffers from an unfortunate case of having an artist who provides vastly more interesting cover work than interior work. While I appreciate great cover work, I would never condemn a book for its cover. But when you look at how many other Vertigo books invite very expressive artists to provide beautiful covers for books with dissimilar interior artists, you find that the gap is wide enough to judge each separately. For Air, Perker's covers are colored in a much finer manner than his interiors, which helps to distract from his figure work shortcomings. Even with that complaint aside, his choice of framing often felt just a little stilted and unoriginal. You don't have to redefine the rules every time you pick up a pencil, but the panel staging could be a little more dynamic. I felt like he hit his stride more confidently when the more visually appealing airships came in at the end of this volume, but it felt like too little, too late for me.

The art, provided by the Turkish M.K. Perker, is solid but I didn't personally feel it was exceptional. As pointed out by a review quoted on the Wikipedia page for Air, his work is very reminiscent of an early Brandon Peterson. I'm a fan of Peterson's hyper-detailed, heavily cross-hatched work, but Perker's is less meticulous and occasionally inconsistent. Faces tend to distort, and detail rapidly disappears as the panel pans outward. I feel that Air suffers from an unfortunate case of having an artist who provides vastly more interesting cover work than interior work. While I appreciate great cover work, I would never condemn a book for its cover. But when you look at how many other Vertigo books invite very expressive artists to provide beautiful covers for books with dissimilar interior artists, you find that the gap is wide enough to judge each separately. For Air, Perker's covers are colored in a much finer manner than his interiors, which helps to distract from his figure work shortcomings. Even with that complaint aside, his choice of framing often felt just a little stilted and unoriginal. You don't have to redefine the rules every time you pick up a pencil, but the panel staging could be a little more dynamic. I felt like he hit his stride more confidently when the more visually appealing airships came in at the end of this volume, but it felt like too little, too late for me. As it stands, Air seems overly eager to get its interesting ideas across without suitably setting up its fictional world. My interests are piqued by the last page reveal, but they're not $9.99 piqued, so I likely will not be flying Clearfleet Airlines again anytime soon.

As it stands, Air seems overly eager to get its interesting ideas across without suitably setting up its fictional world. My interests are piqued by the last page reveal, but they're not $9.99 piqued, so I likely will not be flying Clearfleet Airlines again anytime soon.